As an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teacher, my CV listed many jobs. Experienced colleagues reassured me this was common in the EFL world. Why did I change jobs?

As an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teacher, my CV listed many jobs. Experienced colleagues reassured me this was common in the EFL world. Why did I change jobs?

I left Indonesia because my mother was dying, I left South Korea once when my father was dying. But searching for photos on old hard drives, I was shocked to read the many arguments I had had with employers!

I was from a severely dysfunctional family: the sixth of seven daughters with a swearing alcoholic father and a chronically depressed mother living the American dream in a Chicago lower class suburb. Without brothers, I became aggressive (unlady-like) to survive. I wanted out.

I was from a severely dysfunctional family: the sixth of seven daughters with a swearing alcoholic father and a chronically depressed mother living the American dream in a Chicago lower class suburb. Without brothers, I became aggressive (unlady-like) to survive. I wanted out.

As a university teacher in Michigan, the maze of unwritten middle-class social rules mystified me. I had never learned the value of social lies, and have always been terribly honest, without middle-class diplomacy. Additionally, I retained my childhood’s passionate emotions even after I sought middle-class kingdom with a Bachelors, and then a Masters and teaching license.

In Asia, the teaching reality was “Make the students happy. If they like you, your contract gets renewed.”

In Arabia: “Don’t worry, just pass the students.”

In Turkey, for one class, a Scottish colleague and I thought only four of 22 students should pass. The administration ‘massaged the grades’. Eighteen passed.

Here’s why I changed jobs often.

First, education in developing countries, back in 1984, was a new experience for the locals (slang, the native people). Like the USA more than 2-300 years ago, the only book most Americans owned was the Bible. In Arabia, the Koran. Deserts offer few resources other than oil. My lower-class background helped me understand many Gulf Arabs who had been poor, then became suddenly rich. For example, male bus drivers drove us women teachers to King Saud University women’s campus. One time, the schedule was altered. I figured the bus driver would be late. Why? People raised in poverty usually do not adjust well to sudden changes in routine. He didn’t arrive for an hour. Of course, we teachers, and not the male driver, were lectured for not arriving to college on time.

Second, the amount of corruption and incompetence was and remains astronomical. With so much money flowing into education, many greedy hands grab for the riches. Most work environments reeked of fake degrees, doctored CVs, incompetent managers, people who said they spoke English but did not, few books, and little understanding of syllabi.

Third, colleagues and supervisors were as hazardous as housing situations. Ex-pat life included married couples contemplating divorce, alcoholics hiding out from family, and fake-degreed teachers and supervisors. One time I walked into the classroom of a teacher I respected. Upon the whiteboard, was the chart and questions that would appear on their exam in two days.

Saudi demanded roommates in two-bedroom flats (UK English for ‘apartments’) within fenced-in compounds. Indonesia housed five teachers in one house, with one air-conditioned bedroom. Korea threw me into a spaciously large high-rise apartment – where two married couples lived. The commute to work? More than an hour on the subway which included walking up and down more than 135 stairs. Each way. Taiwan offered a tiny one room with a bathroom suite, situated between two other flats with thin walls. Only the UAE and Oman provided privacy for teachers, often in spacious flats or rented homes.

Fourth, I was a single woman without the protection of a husband. Students in Arabia were more respectful to male teachers. Men could come to college reeking of alcohol, but nothing was said. A woman makes any mistake and she’s reprimanded.

Additionally, male supervisors and colleagues can behave as badly as they want, give me high-stress work schedules, and expect perfection. No man was going to challenge them and fight for me.

In Oman, I was sexually harassed by a male colleague. None of my colleagues or the head of the department stopped or warned him to behave. Fat, in my fifties and flattered, I eventually said, ‘Yes’. At the end of the school year, I was transferred to a different college.

Ten years later, both of us were employed at new Omani university. He had climbed the ladder into Administration. The second time he began his onslaught, I said, ‘No.’

An official from the Omani Ministry of Education addressed about 50 teachers at our college, a mixed group of mostly Filipino and Indian teachers with a smattering of Brits, Americans, and a few locals. The official asked, “Why are students graduating who can’t speak English?”

I wanted to stand and demand the right to fail students! Grades were changed, expectations lowered, a passing grade of 50%, even 40% was considered. And someone from the ministry has the audacity to blame the problem on us English teachers?!

Asian education demanded teachers to please the students. But Asian students often worked hard and learned. On the other hand, Arabic systems expected teachers to produce impossible feats. Arabic managers changed grades to present spectacular results although students seriously lacked study skills and a work ethic. If I were in management, I would rarely, if ever, hire anyone from a Gulf university, or from Turkey.

Too many colleagues and supervisors were impossible to respect, causing arguments about tests, syllabi, courses, requirements, and more. The Arabian view of education: “They’re not used to studying (laziness) so we should just pass them to keep them happy.”

One couple managed 14 years in the UAE; while another had three children and has managed 20 years there. Other teachers keep their mouths shut and pretend to teach and last much longer than I.

All in all, Asian students were excellent, but I didn’t like the slave-mentality built into Asian culture. Arabic students were mostly lazy, but the culture (and weather) were attractive. Still, I am rather shocked at the amount of trouble I caused myself.

So why did I continue?

So why did I continue?

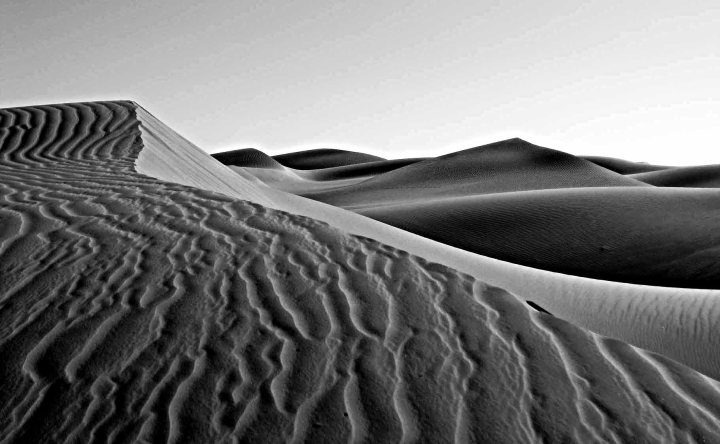

In Arabia, I loved the weather and the desert, as seen in these photos.

I tried to find work in the USA, but failed. A tax-free income, free housing, round-trip air flights home yearly – overseas jobs offered financial freedom and the opportunity to live in exotic locations. The income put me into the middle class. My brain craved the excessive stimulation Asian and Arabic cultures provided. My intellect rejoiced in deciphering seemingly bizarre logic behind cultural norms. All in all, living overseas was a grand adventure.

Unfortunately, by the 15th year, the price for exotica was like 80% stress for 20% novelty. By the 25th year, I no longer trusted people. I had little respect for educational systems. Nearly all my bosses were monsters. I had nearly no social life. My sense of self had been destroyed.

Unlike Indian and Filipino colleagues, my savings would support me at home for six months. However, third world colleagues returned to their birthplaces, built homes and lived rich lives within their communities.

Furthermore, I changed jobs often. I returned to the States, looked for a job, wages were stagnant and rents high. I went overseas again. This made it impossible to accumulate savings. However, I contributed to a pension plan from my first full-time university job in Michigan. This pension allows me a comfortable 11-year income from 65 to about 76 or so – but only living outside the USA. At 77, I sink into poverty. Before old age cripples my mind and body, I imagine various plans for my planetary escape.

In the meantime, I write THE EXPATS: 1,001 Arabian Days & Nights – a novel integrating all of the above.

Do I regret my choices? No.

I regret that youthful idealism is too often destroyed – even killed – by adult reality.

I enjoyed reading about all of your experiences!

LikeLiked by 1 person